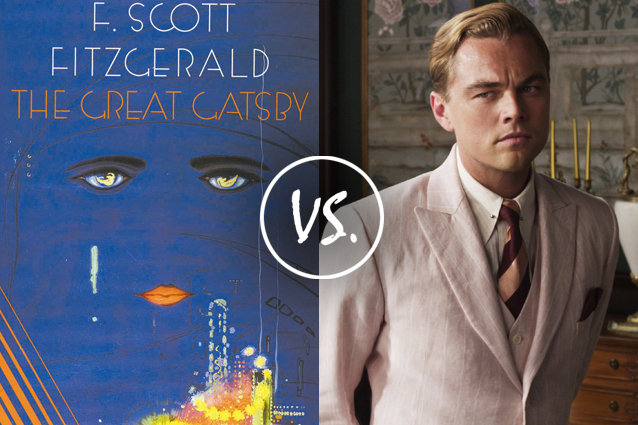

Charles Scribner's Sons; Warner Bros.

Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby was never going to be perfect. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s great American novel

is a cornerstone of most American teenagers’ introduction into

literature, a deeply subtle book that’s so nuanced and delicate, it’s

as if it was specifically built to resist filmmakers. Luhrmann’s 3D

film, while diverting, cannot escape this obstacle.Conveying the ways in which Jay Gatsby’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) “romance” with Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan) is a figment of his own ambition is essential to the story. As is the sheer capitalist nature of Gatsby’s infatuation, his own imperfection, and the unreliability of a narrator who so deeply admires Gatsby in every way. All of these elements dance lightly and deliberately to create a man who serves as the embodiment of the dangers of the American Dream. In the romantic, splashy summer blockbuster, those subtle elements are replaced by broad, bright brushstrokes that tell us when to think and feel, but wind up missing the heart and soul of Fitzgerald’s tragic novel.

Now, I’m not an insane bookworm hell-bent on taking down films that attempt to bastardize the bound works of great women and men. I understand that a film is an interpretation of a book, and that inherently, they cannot be identical. The film can, however, be faithful. And while DiCaprio was working his darndest to hold onto the soul of the book, there are four things Luhrmann could have kept from the text to make that process a whole lot easier:

Warner Bros.

The Elevator Scene That Spurred a Thousand English EssaysAt the press junket for The Great Gatsby at the Plaza in New York, DiCaprio spoke about the weight of a project such as Gatsby. “It’s American Shakespeare,” he said. There are similarities in the deliberate nature of both Shakespeare’s works and Fitzgeralds. Both writers wrote brief compositions, rendering every last syllable a precious one. Therefore, no paragraph – no matter how tiny – is insignificant. Every moment means something.

It’s funny then, that one of the most discussed scenes in the book was missing from Luhrmann’s film. After Nick (played by Tobey Maguire in the movie) goes on a bender with Tom and his mistress Myrtle (Isla Fisher), Nick leaves the party with a Mr. McKee, though he was presumably expected to get loose with Myrtle’s flirtatious sister. When they step into the elevator, the operator asks Mr. McKee to stop touching the lever, and when McKee replies he didn’t know he was touching it, there’s a tinge of homoerotic tension that has confounded readers for years. That moment is followed by pregnant ellipses that lead to Nick, standing in his underwear next to McKee’s bed while McKee shows him his photographs.

In the film, this becomes Nick making out savagely with Myrtle’s sister and waking up in his underwear on his own front porch. The simplficication of the scene drums up a bit of an issue for some interpretations of the novel: this potentially gay or bisexual interlude makes us question Nick’s narration as a reader. When he’s singing these bombastic praises of Gatsby, we have to wonder how much of his description is affected by his affection for Gatsby, and by bringing up this potential question of sexual preference, we could question just how far that affection goes.

It’s not essential to the plot, but it would help the film to convey the deeper complexities of the friendship between Gatsby and Nick, which is, in a way, the heart of the novel.

Warner Bros.

Daisy Buchanan is Not That InnocentHooking mass audiences for a period piece of this size and scale without a sweeping romance would be near impossible. And serving up Daisy exactly as she is written is problematic; she’s a lot harder to fall in love with when we’re aware of her true nature. But Daisy isn't a wolf in doe’s clothing. She has affection for and at times, definitely loves Gatsby, but it’s shallow. It’s something Mulligan’s more sympathetic Daisy skirts a bit. Her Daisy is more of a victim of a bird cage built by her surroundings than a woman whose heart simply isn’t as big as her engrossing personality suggests.

In the book, we see this when Daisy visits with her daughter when Gatsby comes to the Buchanans’ home for lunch. She plays with the child, remarks at how beautiful she is, and then sends her away with her nanny. The child isn’t a part of her soul, something most mothers can’t bear to live without. Instead, the sunny little imp is her plaything, and she comes out when it suits her and goes back to her surrogate mother when Daisy is done.

Adding this moment into the film might have made Daisy unlikeable, which wouldn’t work for Luhrmann’s set up of the big moment in which Tom finds out Gatsby and Daisy have been canoodling at Gatsby’s mansion. However, it would have made the scene more true and far less soapy. When Daisy says she loved Tom and she loved Gatsby, Gatsby’s world is shattered by the disapperance of Daisy as his one true North. How could she love both of them? Could it be, she’s not who he thinks she is? But but it's not until this point and the subsquent scene in which Daisy runs over Myrtle that we can really make the film's Daisy out to be what she really is. The book makes quicker work of it.

Even in the famous shirt-throwing scene, in which Daisy cries “I’ve never seen – I’ve never seen such beautiful shirts before” as Gatsby showers her with his expensive shirts as a means of proving his wealth, Mulligan’s portrayal of the scene makes it seem as though she’s crying about her missed time with Gatsby. In the book, that scene plays with uncertainty: it’s possible that she’s really just upset she missed out on the greater wealth on Gatsby’s side of the bay.

Luhrmann softened Daisy so she wouldn’t put audiences off, but in the end, it means the film is working with a shell of the character that should be Gatsby’s undoing.

Warner Bros.

Tom Is Not The DevilPart of the reason Daisy is so forgivable in this film is that her husband Tom (Joel Edgerton) is so God awful. Whereas Tom was always a bad guy in the novel (cheating on one’s wife constantly isn’t exactly the most admirable of traits, nor is Tom’s rampant racism), he’s a super villain in Luhrmann's film.

The biggest issues are Tom’s moment with Myrtle’s husband following her death and the scene in which Daisy and Tom ignore Nick’s invitation to Gatsby’s funeral.

The moment with Myrtle’s husband Wilson is changed from the novel, expunging Wilson’s fact-finding mission leading him to Gatsby’s pool (where he murders the young billionaire), and instead has Tom practically place the tools for murder into Wilson’s greased up hands like some sort of plot-quickening pixie. In the book, Tom simply tells Wilson the car that killed his wife was yellow (which is what leads him, independently, to Gatsby), but in the film, Tom takes on a persona not unlike Billy Zane’s crass billionaire in Titanic. He tells Wilson outright that Gatsby killed Myrtle, which sends Wilson right over to Gatsby’s in a plan so simple, you’d think Tom would do anything to get revenge on Gatsby. He’s gone from brutish husband to Wicked Willy tying Gatsby to the railroad tracks with one swift motion.

Instead of Gatsby’s downfall being a result of his own unwarranted, amoral fiscal ambition, it’s all because of Tom, who practically gave Wilson a map to Gatsby’s house and loaded his gun for him. That goes against the point of Gatsby’s character, which is to serve as a warning about the dangers of American ambition. Gatsby propelled himself towards his end, not some jealous husband.

Later, when Gatsby has died, Tom has Daisy and their daughter packed up and refusing Nick’s phone calls, but one longing look from Daisy as Tom orders the phone to be hung up signals that Tom has her in a sort of vice. She seems more a prisoner than a woman whose vapid charms ruined a man. She’s too sympathetic, Tom’s too evil, and Gatsby is too blameless.

Warner Bros.

The Ballad of Gatsby and Daisy Is Missing An Essential Element: CapitalismThe passage in which Nick describes Gatsby falling in love with Daisy includes language so financial in nature that it exposes the truth of what Daisy represents for Gatsby. Swathed in romantic moments of longing for even a slight graze of Daisy’s hand, Nick says that Gatsby “had taken her under false pretenses” and later says that Gatsby didn’t know “how extraordinary a ‘nice’ girl could be,” suggesting that he’s traded in lesser ladies before Daisy.

While Gatsby winds up head over heels in love by the end of the passage, the phrasing is tinged with the idea of trading and goods. Gatsby moved up to a nice girl, a rich girl his station didn’t afford him before. And this idealistic, ambitious-to-a-fault young man fell in love with a beautiful girl, and more importantly he fell in love with what her requited love would mean for his life. He wouldn’t be some poor soldier from North Dakota. He would be man worthy of Daisy’s station by association.

It’s this dream that Gatsby is chasing as he builds his wealth through his gangster-esque activities. While he thinks he’s after Daisy, he’s truly after the success that Daisy represents. He’s in love with the success she represents. And while the film does convey Gatsby’s inability to feel satisfied upon reuniting with Daisy, the pervading question of money and how Daisy is just one rung of the ladder of Gatsby’s yearning for success is muddled and buried a bit by the beauty of a big screen romance.

Luhrmann’s Gatsby is beautiful. It’s fun. It’s an absolute spectacle. But it’s missing these subtle, yet monumental moments and had Luhrmann kept them in, we could be looking at a more dismaying, but far more faithful Gatsby.

No comments:

Post a Comment